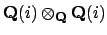

We need only a special case of the tensor product construction.

Let  and

and  be commutative rings containing a field

be commutative rings containing a field  and suppose that

and suppose that  is of finite dimension

is of finite dimension  over

over  , say, with basis

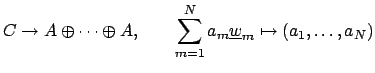

Then

, say, with basis

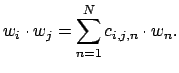

Then  is determined up to isomorphism as a ring over

is determined up to isomorphism as a ring over  by the multiplication table

by the multiplication table

defined by

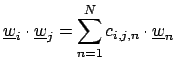

We define a new ring

defined by

We define a new ring  containing

containing  whose elements are

the set of all expressions

where the

whose elements are

the set of all expressions

where the

have the same multiplication rule

as the

have the same multiplication rule

as the  .

.

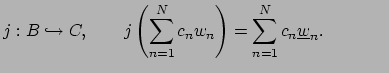

There are injective ring homomorphisms

(note that $

w_1=1$)

and

Moreover  is defined, up to isomorphism, by

is defined, up to isomorphism, by  and

and  and is

independent of the particular choice of basis

and is

independent of the particular choice of basis  of

of  (i.e., a

change of basis of

(i.e., a

change of basis of  induces a canonical isomorphism of the

induces a canonical isomorphism of the  defined by the first basis to the

defined by the first basis to the  defined by the second basis).

We write

since

defined by the second basis).

We write

since  is, in fact, a special case of the ring tensor product.

is, in fact, a special case of the ring tensor product.

Let us now suppose, further, that  is a topological ring, i.e., has

a topology with respect to which addition and multiplication are

continuous. Then the map

is a topological ring, i.e., has

a topology with respect to which addition and multiplication are

continuous. Then the map

defines a bijection between  and the product of

and the product of  copies of

copies of  (considered as sets). We give

(considered as sets). We give  the product topology. It is readily

verified that this topology is independent of the choice of basis

the product topology. It is readily

verified that this topology is independent of the choice of basis

and that multiplication and addition on

and that multiplication and addition on  are

continuous, so

are

continuous, so  is a topological ring. We call this topology

on

is a topological ring. We call this topology

on  the .

the .

Now drop our assumption that  and

and  have a topology, but suppose

that

have a topology, but suppose

that  and

and  are not merely rings but fields. Recall that a

finite extension

are not merely rings but fields. Recall that a

finite extension  of fields is if the number of

embeddings

of fields is if the number of

embeddings

that fix

that fix  equals the degree of

equals the degree of  over

over  , where

, where

is an algebraic closure of

is an algebraic closure of  . The primitive

element theorem from Galois theory asserts that any such extension is

generated by a single element, i.e.,

. The primitive

element theorem from Galois theory asserts that any such extension is

generated by a single element, i.e.,  for some

for some  .

.

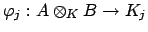

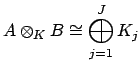

Lemma 18.2.1

Let  and

and  be fields containing the field

be fields containing the field  and suppose

that

and suppose

that  is a separable extension of finite degree

is a separable extension of finite degree ![$ N=[B:K]$](img2121.png) . Then

. Then

is the direct sum of a finite number of fields

is the direct sum of a finite number of fields

, each containing an isomorphic image of

, each containing an isomorphic image of  and an isomorphic

image of

and an isomorphic

image of  .

.

Proof.

By the primitive element theorem, we have

, where

is a

root of some separable irreducible polynomial

![$ f(x)\in K[x]$](img2125.png)

of

degree

. Then

is a basis

for

over

, so

where

are

linearly independent over

and

satisfies

.

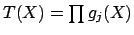

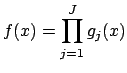

Although the polynomial  is irreducible as an element

of

is irreducible as an element

of ![$ K[x]$](img304.png) , it need not be irreducible in

, it need not be irreducible in ![$ A[x]$](img2131.png) . Since

. Since  is a field, we have a factorization

is a field, we have a factorization

where

![$ g_j(x)\in A[x]$](img2133.png)

is irreducible. The

are

distinct because

is separable (i.e., has distinct

roots in any algebraic closure).

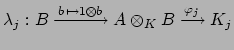

For each  , let

, let

be a root of

be a root of  , where

, where

is a fixed

algebraic closure of the field

is a fixed

algebraic closure of the field  . Let

. Let

.

Then the map

.

Then the map

|

(18.1) |

given by sending any polynomial

in

(where

![$ h\in A[x]$](img2140.png)

)

to

is a ring homomorphism, because the image

of

satisfies the polynomial

, and

![$ A\otimes _K B\cong A[x]/(f(x))$](img2142.png)

.

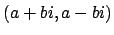

By the Chinese Remainder Theorem, the maps from (18.2.1)

combine to define a ring isomorphism

Each  is of the form

is of the form

![$ A[x]/(g_j(x))$](img2144.png) , so contains an isomorphic

image of

, so contains an isomorphic

image of  . It thus remains to show that the ring

homomorphisms

. It thus remains to show that the ring

homomorphisms

are injections. Since

and

are both fields,

is either the

0 map or injective. However,

is

not the

0 map since

.

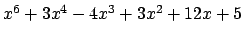

Example 18.2.2

If

and

are finite extensions of

, then

is an algebra of degree

![$ [A:\mathbf{Q}]\cdot [B:\mathbf{Q}]$](img2149.png)

. For example, suppose

is generated by a root of

and

is generated by a root

of

. We can view

as either

![$ A[x]/(x^3-2)$](img2151.png)

or

![$ B[x]/(x^2+1)$](img2152.png)

. The polynomial

is irreducible over

,

and if it factored over the cubic field

, then there would be a

root of

in

, i.e., the quadratic field

would be

a subfield of the cubic field

![$ B=\mathbf{Q}(\sqrt[3]{2})$](img2154.png)

, which is

impossible. Thus

is irreducible over

, so

![$ A\otimes _\mathbf{Q}B

= A.B = \mathbf{Q}(i,\sqrt[3]{2})$](img2155.png)

is a degree

extension of

.

Notice that

contains a copy

and a copy of

. By the

primitive element theorem the composite field

can be generated

by the root of a single polynomial. For example, the minimal

polynomial of

![$ i+\sqrt[3]{2}$](img2157.png)

is

, hence

![$ \mathbf{Q}(i+\sqrt[3]{2})=A.B$](img2159.png)

.

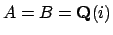

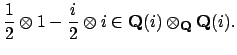

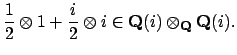

Example 18.2.3

The case

is even more exciting. For example, suppose

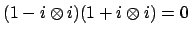

. Using the Chinese Remainder Theorem we have that

since

and

are coprime. The last isomorphism

sends

, with

, to

.

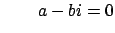

Since

has zero divisors, the tensor

product

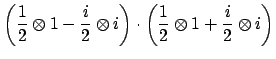

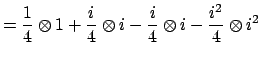

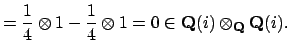

must also have zero divisors.

For example,

and

is a zero divisor pair

on the right hand side, and we can trace back to the elements

of the tensor product that they define. First, by solving

the system

and

we see that

corresponds to

and

, i.e., to the element

This element in turn

corresponds to

Similarly the other element

corresponds to

As a double check, observe that

Clearing the denominator of

and writing

, we have

, so

is a root of the

polynomimal

, and

is not

, so

has

more than

roots.

In general, to understand

explicitly

is the same as factoring either the defining polynomial of

explicitly

is the same as factoring either the defining polynomial of  over the field

over the field  , or factoring the defining polynomial of

, or factoring the defining polynomial of  over

over  .

.

Proof.

We show that both sides of (

18.2.2) are the characteristic

polynomial

of the image of

in

over

.

That

follows at once by computing the characteristic

polynomial in terms of a basis

of

, where

is a basis for

over

(this is

because the matrix of left multiplication by

on

is exactly the same as the matrix of left multiplication on

, so

the characteristic polynomial doesn't change). To see that

, compute the action of the image of

in

with respect to a basis of

|

(18.3) |

composed of basis of the individual extensions

of

. The

resulting matrix will be a block direct sum of submatrices, each of

whose characteristic polynomials is one of the

. Taking

the product gives the claimed identity (

18.2.2).

Corollary 18.2.5

For  we have

and

we have

and

Proof.

This follows from Corollary

18.2.4. First, the norm is

the constant term of the characteristic polynomial, and the constant

term of the product of polynomials is the product of the constant

terms (and one sees that the sign matches up correctly). Second,

the trace is minus the second coefficient of the characteristic

polynomial, and second coefficients add when one multiplies

polynomials:

One could also see both the statements by considering a matrix of

left multiplication by

first with respect to the basis of

and second with respect to the basis coming from the left

side of (

18.2.3).

William Stein

2004-05-06

![]() is a topological ring, i.e., has

a topology with respect to which addition and multiplication are

continuous. Then the map

is a topological ring, i.e., has

a topology with respect to which addition and multiplication are

continuous. Then the map

![]() and

and ![]() have a topology, but suppose

that

have a topology, but suppose

that ![]() and

and ![]() are not merely rings but fields. Recall that a

finite extension

are not merely rings but fields. Recall that a

finite extension ![]() of fields is if the number of

embeddings

of fields is if the number of

embeddings

![]() that fix

that fix ![]() equals the degree of

equals the degree of ![]() over

over ![]() , where

, where

![]() is an algebraic closure of

is an algebraic closure of ![]() . The primitive

element theorem from Galois theory asserts that any such extension is

generated by a single element, i.e.,

. The primitive

element theorem from Galois theory asserts that any such extension is

generated by a single element, i.e., ![]() for some

for some ![]() .

.

![]() is irreducible as an element

of

is irreducible as an element

of ![]() , it need not be irreducible in

, it need not be irreducible in ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is a field, we have a factorization

is a field, we have a factorization

![]() , let

, let

![]() be a root of

be a root of ![]() , where

, where

![]() is a fixed

algebraic closure of the field

is a fixed

algebraic closure of the field ![]() . Let

. Let

![]() .

Then the map

.

Then the map

![$\displaystyle A\otimes _K B \cong A[x]/(f(x)) \cong \bigoplus_{j=1}^J A[x]/(g_j(x))

\cong \bigoplus_{j=1}^J K_j.

$](img2143.png)

![]() is of the form

is of the form

![]() , so contains an isomorphic

image of

, so contains an isomorphic

image of ![]() . It thus remains to show that the ring

homomorphisms

. It thus remains to show that the ring

homomorphisms

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2}- \frac{i}{2} x\in \mathbf{Q}(i)[x]/(x^2+1).$](img2174.png)

![]() explicitly

is the same as factoring either the defining polynomial of

explicitly

is the same as factoring either the defining polynomial of ![]() over the field

over the field ![]() , or factoring the defining polynomial of

, or factoring the defining polynomial of ![]() over

over ![]() .

.![]()