We define two important properties of valuations, both of which

apply to equivalence classes of valuations (i.e., the property

holds for

if and only if it holds for a valuation

equivalent to

if and only if it holds for a valuation

equivalent to

).

).

Definition 15.2.1 (Discrete)

A valuation

is

if there is a

such that for any

Thus the absolute values are bounded away from

.

To say that

is discrete is the same as saying

that the set

forms a discrete subgroup of the reals under addition (because

the elements of the group

is discrete is the same as saying

that the set

forms a discrete subgroup of the reals under addition (because

the elements of the group  are bounded away from 0).

are bounded away from 0).

Proof.

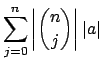

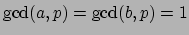

Since

is discrete there is a positive

such that for any positive

we have

.

Suppose

is an arbitrary positive element.

By subtracting off integer multiples of

, we

find that there is a unique

such that

Since

and

, it follows

that

, so

is a multiple of

.

By Proposition 15.2.2, the set

of

for nonzero

for nonzero  is free on one generator, so there

is a

is free on one generator, so there

is a  such that

such that

, for

, for  ,

runs precisely through the set

(Note: we can replace

,

runs precisely through the set

(Note: we can replace  by

by  to see that we

can assume that

to see that we

can assume that  ).

).

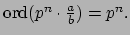

Definition 15.2.3 (Order)

If

, we call

the

of

.

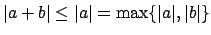

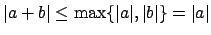

Axiom (2) of valuations

translates into

Definition 15.2.4 (Non-archimedean)

A valuation

is

if we can take

in Axiom (3), i.e., if

|

(15.3) |

If

is not non-archimedean then

it is

.

Note that if we can take  for

for

then we can take

then we can take  for any valuation equivalent to

for any valuation equivalent to

.

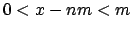

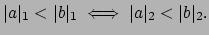

To see that (15.2.1) is equivalent to Axiom (3) with

.

To see that (15.2.1) is equivalent to Axiom (3) with

, suppose

, suppose

. Then

. Then

, so

Axiom (3) asserts that

, so

Axiom (3) asserts that

, which implies

that

, which implies

that

, and conversely.

, and conversely.

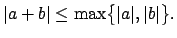

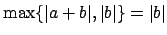

We note at once the following consequence:

Lemma 15.2.5

Suppose

is a non-archimedean valuation.

If

is a non-archimedean valuation.

If  with

with  , then

, then

Proof.

Note that

, which

is true even if

. Also,

where for the last equality we have used that

(if

, then

,

a contradiction).

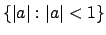

Definition 15.2.6 (Ring of Integers)

Suppose

is a non-archimedean absolute

value on a field

. Then

is a ring called the

of

with respect to

.

Lemma 15.2.7

Two non-archimedean valuations

and

and

are equivalent if and only if they

give the same

are equivalent if and only if they

give the same  .

.

We will prove this modulo the claim (to

be proved later in Section 16.1) that

valuations are equivalent if (and only if) they induce the

same topology.

Proof.

Suppose suppose

is equivalent to

, so

,

for some

. Then

if and only if

, i.e., if

.

Thus

.

Conversely, suppose

.

Then

.

Then

if and only if

if and only if

and

and

, so

, so

|

(15.4) |

The topology induced by

has as basis

of open neighborhoods the set of open balls

for

, and likewise for

. Since

the absolute values

get arbitrarily close

to

0, the set

of open balls

also

forms a basis of the topology induced

by

(and similarly for

).

By (

15.2.2) we have

so the two topologies both have

as

a basis, hence are equal. That equal topologies

imply equivalence of the corresponding valuations

will be proved in Section

16.1.

The set of  with

with  forms an ideal

forms an ideal

in

in  . The

ideal

. The

ideal

is maximal, since if

is maximal, since if  and

and

then

then

, so

, so

, hence

, hence  , so

, so  is a unit.

is a unit.

Lemma 15.2.8

A non-archimedean valuation

is

discrete if and only if

is

discrete if and only if

is a principal ideal.

is a principal ideal.

Proof.

First suppose that

is discrete.

Choose

with

maximal, which

we can do since

so the discrete set

is bounded above.

Suppose

. Then

so

.

Thus

Conversely, suppose

is principal. For any

is principal. For any

we have

we have  with

with  . Thus

. Thus

Thus

is bounded away from

,

which is exactly the definition of discrete.

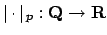

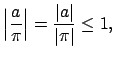

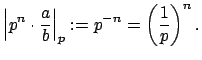

Example 15.2.9

For any prime

, define the

-adic valuation

as follows. Write a nonzero

as

, where

. Then

This valuation is both discrete and non-archimedean.

The ring

is the local ring

which has maximal ideal generated by

. Note that

We will using the following lemma later (e.g., in

the proof of Corollary 16.2.4 and Theorem 15.3.2).

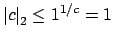

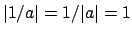

Lemma 15.2.10

A valuation

is non-archimedean if and only if

is non-archimedean if and only if  for all

for all  in the ring generated by

in the ring generated by  in

in  .

.

Note that we cannot identify the ring generated by  with

with

in general, because

in general, because  might have characteristic

might have characteristic  .

.

Proof.

If

is non-archimedean, then

,

so by Axiom (3) with

, we have

. By

induction it follows that

.

Conversely, suppose  for all integer multiples

for all integer multiples  of

of  .

This condition is also true if we replace

.

This condition is also true if we replace

by

any equivalent valuation, so replace

by

any equivalent valuation, so replace

by

one with

by

one with  , so that the triangle inequality holds.

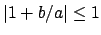

Suppose

, so that the triangle inequality holds.

Suppose  with

with  . Then

by the triangle inequality,

. Then

by the triangle inequality,

Now take

th roots of both sides to get

and take the limit as

to see

that

. This proves that one

can take

in Axiom (3), hence that

is non-archimedean.

William Stein

2004-05-06

![]()

![]() .

Then

.

Then

![]() if and only if

if and only if

![]() and

and

![]() , so

, so

![]() with

with ![]() forms an ideal

forms an ideal

![]() in

in ![]() . The

ideal

. The

ideal

![]() is maximal, since if

is maximal, since if ![]() and

and

![]() then

then

![]() , so

, so

![]() , hence

, hence ![]() , so

, so ![]() is a unit.

is a unit.

![]() is principal. For any

is principal. For any

![]() we have

we have ![]() with

with ![]() . Thus

. Thus

![]() for all integer multiples

for all integer multiples ![]() of

of ![]() .

This condition is also true if we replace

.

This condition is also true if we replace

![]() by

any equivalent valuation, so replace

by

any equivalent valuation, so replace

![]() by

one with

by

one with ![]() , so that the triangle inequality holds.

Suppose

, so that the triangle inequality holds.

Suppose ![]() with

with ![]() . Then

by the triangle inequality,

. Then

by the triangle inequality,