Next: Norms of Ideals Up: Discrimannts, Norms, and Finiteness Previous: Preliminary Remarks Contents Index

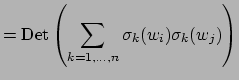

If we consider

![]() instead, we

obtain a number that is a well-defined integer which can

be either positive or negative. Note that

instead, we

obtain a number that is a well-defined integer which can

be either positive or negative. Note that

|

||

If we view ![]() as a

as a

![]() -vector space, then

-vector space, then

![]() defines a bilinear pairing

defines a bilinear pairing

![]() on

on ![]() , which we call

the . The following lemma asserts that this

pairing is nondegenerate, so

, which we call

the . The following lemma asserts that this

pairing is nondegenerate, so

![]() hence

hence

![]() .

.

Warning: In ![]() is defined to be the discriminant of the

polynomial you happened to use to define

is defined to be the discriminant of the

polynomial you happened to use to define ![]() , which is (in my opinion)

a poor choice and goes against most of the literature.

, which is (in my opinion)

a poor choice and goes against most of the literature.

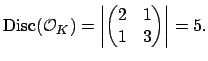

The following proposition asserts that the discriminant of an order

![]() in

in ![]() is bigger than

is bigger than

![]() by a factor of the square

of the index.

by a factor of the square

of the index.

This result is enough to give an algorithm for computing ![]() ,

albeit a potentially slow one. Given

,

albeit a potentially slow one. Given ![]() , find some order

, find some order

![]() , and compute

, and compute

![]() . Factor

. Factor ![]() , and use the factorization

to write

, and use the factorization

to write

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the largest square that

divides

is the largest square that

divides ![]() . Then the index of

. Then the index of ![]() in

in ![]() is a divisor of

is a divisor of ![]() ,

and we (tediously) can enumerate all rings

,

and we (tediously) can enumerate all rings ![]() with

with

![]() and

and

![]() , until we find the largest one all of

whose elements are integral.

, until we find the largest one all of

whose elements are integral.

![$\displaystyle \Disc (\O ) = \left\vert \left(

\begin{matrix}2&0\ 0&10

\end{matrix}\right) \right\vert = 20 = [\O _K:\O ]^2\cdot 5.

$](img764.png)

William Stein 2004-05-06