Recall that the Chinese Remainder Theorem from elementary number

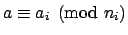

theory asserts that if

are integers that are coprime

in pairs, and

are integers that are coprime

in pairs, and

are integers, then there exists an

integer

are integers, then there exists an

integer  such that

such that

for each

for each

.

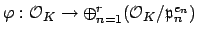

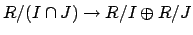

In terms of rings, the Chinese Remainder Theorem asserts that the

natural map

is an isomorphism. This result generalizes to rings of integers of

number fields.

.

In terms of rings, the Chinese Remainder Theorem asserts that the

natural map

is an isomorphism. This result generalizes to rings of integers of

number fields.

Proof.

The ideal

is the largest ideal of

that is divisible

by (contained in) both

and

. Since

and

are coprime,

is divisible by

, i.e.,

. By

definition of ideal

, which

completes the proof.

Remark 9.1.2

This lemma is true for any ring

and ideals

such that

. For the general proof, choose

and

such that

. If

then

so

, and the other inclusion is obvious by definition.

Proof.

First assume that we know the theorem in the case when the

are

powers of prime ideals. Then we can deduce the general case by noting

that each

is isomorphic to a product

, where

, and

is isomorphic to the product of the

,

where the

and

run through the same prime powers as appear

on the right hand side.

It thus suffices to prove that if

are distinct

prime ideals of

are distinct

prime ideals of  and

and

are positive integers,

then

are positive integers,

then

is an isomorphism. Let

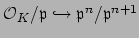

be the natural map induced by reduction mod

. Then kernel of

is

,

which by Lemma

9.1.1 is equal to

, so

is injective. Note that the projection

of

onto each factor is obviously

surjective, so it suffices to show that the element

is in the image of

(and the similar elements for the other

factors). Since

is not divisible

by

, hence not contained in

, there is

an element

with

. Since

is maximal,

is a field, so there exists

such that

, for some

. Then

is congruent to

0 mod

for each

since it is in

, and it

is congruent to

modulo

.

Remark 9.1.4

In fact, the surjectivity part of the above proof is easy to prove

for any commutative ring; indeed, the above proof illustrates how

trying to prove something in a special case can result in a more

complicated proof!! Suppose

is a ring and

are ideals in

such that

. Choose

and

such that

. Then

maps to

in

and

maps to

in

. Thus the map

is surjective. Also, as mentioned above,

.

Example 9.1.5

The

command

ChineseRemainderTheorem implements the

algorithm suggested by the above theorem. In the following example,

we compute a prime over

and a prime over

of the ring of

integers of

![$ \mathbf{Q}(\sqrt[3]{2})$](img632.png)

, and find an element of

that is

congruent to

![$ \sqrt[3]{2}$](img633.png)

modulo one prime and

modulo the other.

> R<x> := PolynomialRing(RationalField());

> K<a> := NumberField(x^3-2);

> OK := MaximalOrder(K);

> I := Factorization(3*OK)[1][1];

> J := Factorization(5*OK)[1][1];

> I;

Prime Ideal of OK

Two element generators:

[3, 0, 0]

[4, 1, 0]

> J;

Prime Ideal of OK

Two element generators:

[5, 0, 0]

[7, 1, 0]

> b := ChineseRemainderTheorem(I, J, OK!a, OK!1);

> b - a in I;

true

> b - 1 in J;

true

> K!b;

-4

The element found by the Chinese Remainder Theorem algorithm in

this case is

.

The following lemma is a nice application of the Chinese Remainder

Theorem. We will use it to prove that every ideal of  can be

generated by two elements. Suppose

can be

generated by two elements. Suppose  is a nonzero integral ideals of

is a nonzero integral ideals of

. If

. If  , then

, then

, so

, so  divides

divides  and

the quotient

and

the quotient  is an integral ideal. The following lemma

asserts that

is an integral ideal. The following lemma

asserts that  can be chosen so the quotient

can be chosen so the quotient  is coprime to

any given ideal.

is coprime to

any given ideal.

Lemma 9.1.6

If  are nonzero integral ideals in

are nonzero integral ideals in  , then there exists

an

, then there exists

an  such that

such that  is coprime to

is coprime to  .

.

Proof.

Let

be the prime divisors of

.

For each

, let

be the largest power of

that divides

. Choose an element

that is not in

(there is such an element

since

, by unique factorization).

By Theorem

9.1.3, there exists

such that

for all

and

also

(We are applying the theorem with the coprime integral ideals

, for

and the integral

ideal

.)

To complete the proof we must show that  is not

divisible by any

is not

divisible by any

, or equivalently, that the

, or equivalently, that the

exactly divides

exactly divides  . Because

. Because

, there is

, there is

such that

such that

. Since

. Since

, it follows that

, it follows that

,

so

,

so

divides

divides  . If

. If

,

then

,

then

, a contradiction, so

, a contradiction, so

does not divide

does not divide  , which completes

the proof.

, which completes

the proof.

Suppose  is a nonzero ideal of

is a nonzero ideal of  . As an abelian group

. As an abelian group  is free of rank equal to the degree

is free of rank equal to the degree

![$ [K:\mathbf{Q}]$](img327.png) of

of  , and

, and  is of

finite index in

is of

finite index in  , so

, so  can be generated as an abelian group,

hence as an ideal, by

can be generated as an abelian group,

hence as an ideal, by

![$ [K:\mathbf{Q}]$](img327.png) generators. The following proposition

asserts something much better, namely that

generators. The following proposition

asserts something much better, namely that  can be generated as an ideal in

can be generated as an ideal in  by at most two elements.

by at most two elements.

Proposition 9.1.7

Suppose  is a fractional ideal in the ring

is a fractional ideal in the ring  of integers of a

number field. Then there exist

of integers of a

number field. Then there exist  such that

such that  .

.

Proof.

If

, then

is generated by

element and we are done. If

is not an integral ideal, then there is

such that

is

an integral ideal, and the number of generators of

is the same as

the number of generators of

, so we may assume that

is an

integral ideal.

Let  be any nonzero element of the integral ideal

be any nonzero element of the integral ideal  . We will

show that there is some

. We will

show that there is some  such that

such that  . Let

. Let  .

By Lemma 9.1.6, there exists

.

By Lemma 9.1.6, there exists  such that

such that  is

coprime to

is

coprime to  . The ideal

. The ideal

is the greatest common

divisor of

is the greatest common

divisor of  and

and  , so

, so  divides

divides  , since

, since  divides

both

divides

both  and

and  . Suppose

. Suppose

is a prime power that divides

is a prime power that divides

, so

, so

divides both

divides both  and

and  . Because

. Because  and

and  are coprime and

are coprime and

divides

divides  , we see that

, we see that

does not divide

does not divide  , so

, so

must divide

must divide  . Thus

. Thus  divides

divides  , so

, so  as claimed.

as claimed.

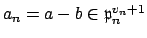

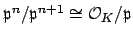

We can also use Theorem 9.1.3 to determine the

-module structure of the successive quotients

-module structure of the successive quotients

.

.

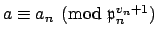

Proposition 9.1.8

Let

be a nonzero prime ideal of

be a nonzero prime ideal of  , and let

, and let  be an

integer. Then

be an

integer. Then

as

as  -modules.

-modules.

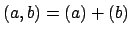

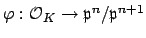

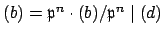

Proof.

(Compare page 13 of Swinnerton-Dyer.)

Since

(by unique factorization), we

can fix an element

such that

. Let

be the

-module morphism defined by

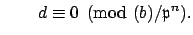

. The kernel of

is

since clearly

and if

then

, so

, so

, since

does not

divide

. Thus

induces an injective

-module

homomorphism

.

It remains to show that  is surjective, and this is where we

will use Theorem 9.1.3. Suppose

is surjective, and this is where we

will use Theorem 9.1.3. Suppose

.

By Theorem 9.1.3 there exists

.

By Theorem 9.1.3 there exists

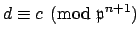

such that

such that

and

We have

since

and

by the second displayed condition, so

, hence

. Finally

so

is surjective.

William Stein

2004-05-06

![]() are distinct

prime ideals of

are distinct

prime ideals of ![]() and

and

![]() are positive integers,

then

are positive integers,

then

![]() can be

generated by two elements. Suppose

can be

generated by two elements. Suppose ![]() is a nonzero integral ideals of

is a nonzero integral ideals of

![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then

![]() , so

, so ![]() divides

divides ![]() and

the quotient

and

the quotient ![]() is an integral ideal. The following lemma

asserts that

is an integral ideal. The following lemma

asserts that ![]() can be chosen so the quotient

can be chosen so the quotient ![]() is coprime to

any given ideal.

is coprime to

any given ideal.

![]() is not

divisible by any

is not

divisible by any

![]() , or equivalently, that the

, or equivalently, that the

![]() exactly divides

exactly divides ![]() . Because

. Because

![]() , there is

, there is

![]() such that

such that

![]() . Since

. Since

![]() , it follows that

, it follows that

![]() ,

so

,

so

![]() divides

divides ![]() . If

. If

![]() ,

then

,

then

![]() , a contradiction, so

, a contradiction, so

![]() does not divide

does not divide ![]() , which completes

the proof.

, which completes

the proof.

![]()

![]() is a nonzero ideal of

is a nonzero ideal of ![]() . As an abelian group

. As an abelian group ![]() is free of rank equal to the degree

is free of rank equal to the degree

![]() of

of ![]() , and

, and ![]() is of

finite index in

is of

finite index in ![]() , so

, so ![]() can be generated as an abelian group,

hence as an ideal, by

can be generated as an abelian group,

hence as an ideal, by

![]() generators. The following proposition

asserts something much better, namely that

generators. The following proposition

asserts something much better, namely that ![]() can be generated as an ideal in

can be generated as an ideal in ![]() by at most two elements.

by at most two elements.

![]() be any nonzero element of the integral ideal

be any nonzero element of the integral ideal ![]() . We will

show that there is some

. We will

show that there is some ![]() such that

such that ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() .

By Lemma 9.1.6, there exists

.

By Lemma 9.1.6, there exists ![]() such that

such that ![]() is

coprime to

is

coprime to ![]() . The ideal

. The ideal

![]() is the greatest common

divisor of

is the greatest common

divisor of ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so ![]() divides

divides ![]() , since

, since ![]() divides

both

divides

both ![]() and

and ![]() . Suppose

. Suppose

![]() is a prime power that divides

is a prime power that divides

![]() , so

, so

![]() divides both

divides both ![]() and

and ![]() . Because

. Because ![]() and

and ![]() are coprime and

are coprime and

![]() divides

divides ![]() , we see that

, we see that

![]() does not divide

does not divide ![]() , so

, so

![]() must divide

must divide ![]() . Thus

. Thus ![]() divides

divides ![]() , so

, so ![]() as claimed.

as claimed.

![]()

![]() -module structure of the successive quotients

-module structure of the successive quotients

![]() .

.

![]() is surjective, and this is where we

will use Theorem 9.1.3. Suppose

is surjective, and this is where we

will use Theorem 9.1.3. Suppose

![]() .

By Theorem 9.1.3 there exists

.

By Theorem 9.1.3 there exists

![]() such that

such that