The following theorem asserts that inequivalent valuations are in fact

almost totally indepedent. For our purposes it will be superseded by

the strong approximation theorem (Theorem 20.4.4).

Proof.

We note first that it will be enough to find, for each

, an

element

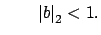

such that

where

. For then as

, we have

It is then enough to take

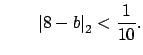

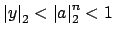

By symmetry it is enough to show the existence of  with

with

We will do this by induction on

.

First suppose  . Since

. Since

and

and

are

inequivalent (and all absolute values are assumed nontrivial)

there is an

are

inequivalent (and all absolute values are assumed nontrivial)

there is an  such that

such that

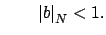

and and |

(16.2) |

and similarly a

such that

and

Then

will do.

Remark 16.3.2

It is not completely clear that

one can choose an

such that (

16.3.1) is satisfied.

Suppose it were impossible. Then because the valuations are

nontrivial, we would have that for any

if

then

. This implies the converse statement: if

and

then

. To see this, suppose there

is an

such that

and

.

Choose

such that

. Then for any integer

we have

, so by hypothesis

. Thus

for all

. Since

we

have

as

, so

, a

contradiction since

. Thus

if and only if

, and we have proved before that this implies that

is equivalent to

.

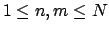

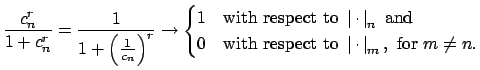

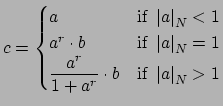

Next suppose  . By the case

. By the case  , there is an

, there is an  such

that

such

that

By the case for

there is a

such that

and

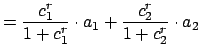

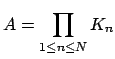

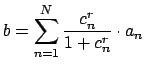

Then put

where

is sufficiently large so that

and

for

.

Example 16.3.3

Suppose

, let

be the archimedean absolute value

and let

be the

-adic absolute value. Let

,

, and

, as in the remark right after

Theorem

16.3.1. Then the theorem implies that there

is an element

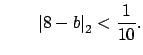

such that

and

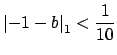

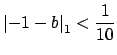

As in the proof of the theorem, we can find such a

by finding

a

such that

and

, and

a

and

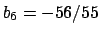

. For example,

and

works, since

and

and

and

. Again

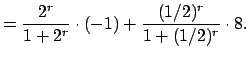

following the proof, we see that for sufficiently large

we can take

We have

,

,

,

,

,

. None of the

work for

,

but

works.

![]() and the

and the

![]() are

are ![]() -adic valuations,

Theorem 16.3.1 is related to the Chinese Remainder

Theorem (Theorem 9.1.3), but the strong approximation theorem

(Theorem 20.4.4) is the

real generalization.

-adic valuations,

Theorem 16.3.1 is related to the Chinese Remainder

Theorem (Theorem 9.1.3), but the strong approximation theorem

(Theorem 20.4.4) is the

real generalization.

![]() with

with

![]() . Since

. Since

![]() and

and

![]() are

inequivalent (and all absolute values are assumed nontrivial)

there is an

are

inequivalent (and all absolute values are assumed nontrivial)

there is an ![]() such that

such that

![]() . By the case

. By the case ![]() , there is an

, there is an ![]() such

that

such

that

and

and